Blog Categories

- African Incidents

- Atlantis Incidents

- Australian Incidents

- Belgian Incidents

- Bermuda Triangle Incidents

- Brazilian Incidents

- Canadian Incidents

- Chinese Incidents

- European Incidents

- France Incidents

- Ghosts

- Giants

- Italy Incidents

- Japanese Incidents

- Middle East Incidents

- Portugal Incidents

- Project Serpo

- Puerto Rico Incidents

- Russian Incidents

- Sasquatch

- Scandinavia Incidents

- Spanish Incidents

- UFOs

- United Kingdom Incidents

- United States Incidents

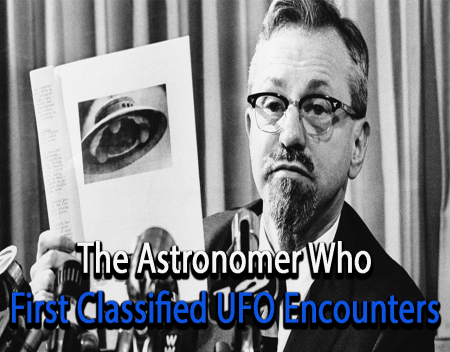

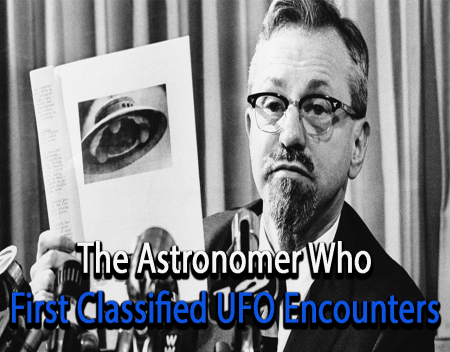

The Astronomer Who First Classified UFO Close Encounters

It’s September 1947, and the U.S. Air Force has a problem. A rash of reports about mysterious objects in the skies has the public on edge and the military baffled. The Air Force needs to figure out what’s going on—and fast. It launches an investigation it calls Project Sign.

By early 1948 the team realizes it needs some outside expertise to sift through the reports it was receiving—specifically an astronomer who can determine which cases are easily explained by astronomical phenomena, such as planets, stars, or meteors.

For J. Allen Hynek, then the 37-year-old director at Ohio State University’s McMillin Observatory, it would be a classic case of being in the right place at the right time—or, as he may have occasionally lamented, the wrong place at the wrong one.

Hynek had worked for the government during the war, developing new defense technologies like the first radio-controlled fuse, so he already had a high-security clearance and was a natural go-to.

“One day I had a visit from several men from the technical center at Wright-Patterson Air Force base, which was only 60 miles away in Dayton,” Hynek later wrote. “With some obvious embarrassment, the men eventually brought up the subject of ‘flying saucers’ and asked me if I would care to serve as a consultant to the Air Force on the matter… The job didn't seem as though it would take too much time, so I agreed.”

Little did Hynek realize that he was about to begin a lifelong odyssey that would make him one of the most famous and, at times, controversial scientists of the 20 century. Nor could he have guessed how much his own thinking about UFOs would change over that period as he persisted in bringing rigorous scientific inquiry to the subject.

“I had scarcely heard of UFOs in 1948 and, like every other scientist I knew, assumed that they were nonsense,” he recalled.

Project Sign ran for a year, during which the team reviewed 237 cases. In Hynek’s final report, he noted that about 32 percent of incidents could be attributed to astronomical phenomena, while another 35 percent had other explanations, such as balloons, rockets, flares or birds. Of the remaining 33 percent, 13 percent didn’t offer enough evidence to yield an explanation. That left 20 percent that provided investigators with some evidence but still couldn’t be explained.

The Air Force was loath to use the term “unidentified flying object,” so the mysterious 20 percent were simply classified as “unidentified.”

In February 1949, Project Sign was succeeded by Project Grudge. While Sign offered at least a pretense of scientific objectivity, Grudge seems to have been dismissive from the start, just as its angry-sounding name suggests. Hynek, who played no role in Project Grudge, said it “took as its premise that UFOs simply could not be.” Perhaps not surprisingly, its report, issued at the end of 1949, concluded that the phenomena posed no danger to the United States, having resulted from mass hysteria, deliberate hoaxes, mental illness, or conventional objects that the witnesses had misinterpreted as otherworldly. It also suggested the subject wasn’t worth further study.

That might’ve been the end of it. But UFO incidents continued, including some puzzling reports from the Air Force’s own radar operators. The national media began treating the phenomenon more seriously; LIFE magazine did a 1952 cover story, and even the widely respected TV journalist Edward R. Murrow devoted a program to the topic, including an interview with Kenneth Arnold, a pilot whose 1947 sighting of mysterious objects over Mount Rainier in Washington state popularized the term “flying saucer.” The Air Force had little choice but to revive Project Grudge, which soon morphed into the more benignly named Project Blue Book.

Hynek joined Project Blue Book in 1952 and would remain with it until its demise in 1969. For him, it was a side gig as he continued to teach and to pursue other, non-UFO research, at Ohio State. In 1960 he moved to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, to chair its astronomy department.

As before, Hynek’s role was to review the reports of UFO sightings and determine whether there was a logical astronomical explanation. Typically that involved a lot of unglamorous paperwork; but now and then, for an especially puzzling case, he had a chance to get out into the field.

There he discovered something he might never have learned from simply reading the files: how normal the people who reported seeing UFOs tended to be. “The witnesses I interviewed could have been lying, could have been insane, or could have been hallucinating collectively—but I do not think so,” he recalled in his 1977 book, The Hynek UFO Report.

“Their standing in the community, their lack of motive for the perpetration of a hoax, their own puzzlement at the turn of events they believe they witnessed, and often their great reluctance to speak of the experience—all lend a subjective reality to their UFO experience.”

For the rest of his life, Hynek would deplore the ridicule that people who reported a UFO sighting often had to endure—which, in turn, caused untold numbers of others to never come forward. It wasn’t just unfair to the individuals involved but meant a loss of data that might be useful to researchers.

“Given the controversial nature of the subject, it’s understandable that both scientists and witnesses are reluctant to come forward,” says Jacques Vallee, co-author with Dr. Hynek of The Edge of Reality: A Progress Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. “Because their life is going to change. There are cases where their house is broken into. People throw stones at their kids. There are family crises—divorce and so on… You become the person who has seen something that other people have not seen. And there is a lot of suspicions attached to that.”

SOURCE: history.com

It’s September 1947, and the U.S. Air Force has a problem. A rash of reports about mysterious objects in the skies has the public on edge and the military baffled. The Air Force needs to figure out what’s going on—and fast. It launches an investigation it calls Project Sign.

By early 1948 the team realizes it needs some outside expertise to sift through the reports it was receiving—specifically an astronomer who can determine which cases are easily explained by astronomical phenomena, such as planets, stars, or meteors.

For J. Allen Hynek, then the 37-year-old director at Ohio State University’s McMillin Observatory, it would be a classic case of being in the right place at the right time—or, as he may have occasionally lamented, the wrong place at the wrong one.

Hynek had worked for the government during the war, developing new defense technologies like the first radio-controlled fuse, so he already had a high-security clearance and was a natural go-to.

“One day I had a visit from several men from the technical center at Wright-Patterson Air Force base, which was only 60 miles away in Dayton,” Hynek later wrote. “With some obvious embarrassment, the men eventually brought up the subject of ‘flying saucers’ and asked me if I would care to serve as a consultant to the Air Force on the matter… The job didn't seem as though it would take too much time, so I agreed.”

Little did Hynek realize that he was about to begin a lifelong odyssey that would make him one of the most famous and, at times, controversial scientists of the 20 century. Nor could he have guessed how much his own thinking about UFOs would change over that period as he persisted in bringing rigorous scientific inquiry to the subject.

“I had scarcely heard of UFOs in 1948 and, like every other scientist I knew, assumed that they were nonsense,” he recalled.

Project Sign ran for a year, during which the team reviewed 237 cases. In Hynek’s final report, he noted that about 32 percent of incidents could be attributed to astronomical phenomena, while another 35 percent had other explanations, such as balloons, rockets, flares or birds. Of the remaining 33 percent, 13 percent didn’t offer enough evidence to yield an explanation. That left 20 percent that provided investigators with some evidence but still couldn’t be explained.

The Air Force was loath to use the term “unidentified flying object,” so the mysterious 20 percent were simply classified as “unidentified.”

In February 1949, Project Sign was succeeded by Project Grudge. While Sign offered at least a pretense of scientific objectivity, Grudge seems to have been dismissive from the start, just as its angry-sounding name suggests. Hynek, who played no role in Project Grudge, said it “took as its premise that UFOs simply could not be.” Perhaps not surprisingly, its report, issued at the end of 1949, concluded that the phenomena posed no danger to the United States, having resulted from mass hysteria, deliberate hoaxes, mental illness, or conventional objects that the witnesses had misinterpreted as otherworldly. It also suggested the subject wasn’t worth further study.

That might’ve been the end of it. But UFO incidents continued, including some puzzling reports from the Air Force’s own radar operators. The national media began treating the phenomenon more seriously; LIFE magazine did a 1952 cover story, and even the widely respected TV journalist Edward R. Murrow devoted a program to the topic, including an interview with Kenneth Arnold, a pilot whose 1947 sighting of mysterious objects over Mount Rainier in Washington state popularized the term “flying saucer.” The Air Force had little choice but to revive Project Grudge, which soon morphed into the more benignly named Project Blue Book.

Hynek joined Project Blue Book in 1952 and would remain with it until its demise in 1969. For him, it was a side gig as he continued to teach and to pursue other, non-UFO research, at Ohio State. In 1960 he moved to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, to chair its astronomy department.

As before, Hynek’s role was to review the reports of UFO sightings and determine whether there was a logical astronomical explanation. Typically that involved a lot of unglamorous paperwork; but now and then, for an especially puzzling case, he had a chance to get out into the field.

There he discovered something he might never have learned from simply reading the files: how normal the people who reported seeing UFOs tended to be. “The witnesses I interviewed could have been lying, could have been insane, or could have been hallucinating collectively—but I do not think so,” he recalled in his 1977 book, The Hynek UFO Report.

“Their standing in the community, their lack of motive for the perpetration of a hoax, their own puzzlement at the turn of events they believe they witnessed, and often their great reluctance to speak of the experience—all lend a subjective reality to their UFO experience.”

For the rest of his life, Hynek would deplore the ridicule that people who reported a UFO sighting often had to endure—which, in turn, caused untold numbers of others to never come forward. It wasn’t just unfair to the individuals involved but meant a loss of data that might be useful to researchers.

“Given the controversial nature of the subject, it’s understandable that both scientists and witnesses are reluctant to come forward,” says Jacques Vallee, co-author with Dr. Hynek of The Edge of Reality: A Progress Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. “Because their life is going to change. There are cases where their house is broken into. People throw stones at their kids. There are family crises—divorce and so on… You become the person who has seen something that other people have not seen. And there is a lot of suspicions attached to that.”

SOURCE: history.com